Background Information

It is well known that the mind regulates our perceptions of pain. There are many mental strategies that can be used to reduce the perception of pain. For example, distraction (for example, listening to music), or techniques that calter the context of the experience (hypnosis, cognitive reappraisal, or even a placebo).

Further research indicates that meditation can also reduce the perception of pain through acceptance and mindfulness. Instead of striving to distract, ignore or reframe, meditation instead cultivates states of open acceptance and non-judgmental awareness of the present moment. This is thought to reduce the perception of pain by reducing the emotional reaction to it.

Techniques such as Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (

MBSR

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) is a program designed to help individuals cope with stress, pain, and illness. Developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the 1970s, it combines meditation and yoga to promote awareness and stress management. The eight-week program teaches participants to focus on the present moment non-judgmentally, enhancing their ability to manage difficulties.

More on Wikipedia

View in glossary

) and Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) have been shown to decrease pain unpleasantness and lead to a reduction of symptoms in chronic pain patients.

This study aimed to investigate the neural mechanisms underlying the effects of open awareness meditation on pain perception, focusing on the amygdala and the so-called “salience network”, a set of regions in the brain thought to be responsible for detection and integration of emotional and sensory stimuli, as well as in modulating the switch between the internally directed cognition of the default mode network (

DMN

The default mode network (DMN) is a system of connected brain areas that show increased activity when a person is not focused on what is happening around them. such as during daydreaming and mind-wandering. It can also be active when the individual is thinking about others or themselves, remembering the past, and planning for the future.

More on Wikipedia

View in glossary

) and externally directed cognition.

What They Did

The researchers compared the neural mechanisms of pain perception between expert meditators and novice participants using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The study group consisted of 14 long-term Buddhist practitioners, each with over 10,000 hours of meditation experience, and 14 control subjects who had no prior experience with meditation. The central focus was on the effects of Open Presence (OP) meditation, a practice aimed at cultivating a state of acceptance and openness, on the participants’ experience of pain. Participants were exposed to both painful and non-painful thermal stimuli while undergoing

fMRI

An fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) measures changes in blood flow related to neural activity in the brain, offering insights into brain function and activity patterns.

More on Wikipedia

View in glossary

scans, allowing the researchers to observe the brain’s response to pain and meditation in real time.

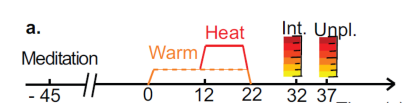

The experimental design included a detailed calibration process to determine the temperature threshold for pain stimuli for each participant, ensuring a consistent pain experience across the study. Participants received comprehensive instructions on the meditation practices to be employed during the experiment, with control subjects being given a brief training period to familiarize themselves with the meditation technique. The researchers analyzed the data to assess differences in pain intensity and unpleasantness ratings between the two groups, along with examining the brain’s activity in response to pain. Key areas of investigation included the effect of meditation on anticipatory neural activity related to pain, the correlation between such activity and pain perception, and how meditation practice influences baseline brain activity and neural habituation to pain stimuli. This approach allowed for a nuanced understanding of how meditation impacts the neural processing of pain and the potential benefits of mindfulness practices in pain management.

One Big Result

To summarize this paper down into one oversimplified takeaway:

Compared to novices, expert meditators reported less unpleasantness during pain.

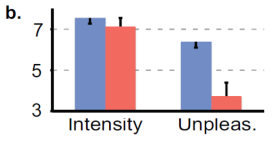

What does this mean? Here are the intensity and unpleasantness ratings for both groups

This is an extremely clear finding: Meditation decreases the perceived unpleasantness of pain. The meditators also showed enhanced activity in the salience network during the painful event, indicating that they were more aware of the pain, but less emotionally reactive to it.

As an additional finding, the pain trials were repeated on each user a number of times, and the meditators underwent more rapid habituation to the pain stimuli than the novices. That is: Even after an experience had been demonstrated safe by repeated exposure, the novices would continue to show the same anxiety response to it, while the meditation group would habituate to the experience and show less anxiety.

The attentional mechanisms observed here may relate to Shields et al.’s (2020) findings on meditation’s effects on controlled attention processes, suggesting enhanced attentional control may contribute to altered pain perception. Given Davidson, Kabat-Zinn et al.’s (2003) findings on meditation’s effects on brain activity and immune function, future research might explore whether pain perception changes correlate with broader biological markers of health.

Miscellaneous Interesting Takeaways

Anticipation and the Two Arrows

There is a teaching in buddhism that has stuck with me ever since I first heard it, the story of the two arrows. According to this teaching, the Buddha described that when we are struck by an arrow, it is painful. This arrow represents whatever initial suffering or pain that we experience from life’s inevitable challenges, such as illness, loss, or disappointment.

However, we often compound our suffering by the way we react to the first arrow. This reaction is likened to being struck by a second arrow. While the first arrow’s pain is unavoidable, the second arrow represents the additional suffering we create for ourselves through our reactions, such as anger, frustration, self-pity, or resentment. Unlike the first arrow, the pain from the second arrow is not inevitable; it arises from our attachment, aversion, and ignorance.

Anxiety about pain that we know is safe is pretty much the definition of a second arrow. The authors tested a hypothesis related to the two arrows:

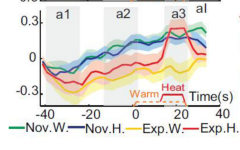

Our second hypothesis was that experts would display less anxiety-related anticipatory activity in the amygdala and salience network prior to pain compared to novices, as a result of the present-centered nature of this state

The following image shows the brain activity of the two groups during the anticipation of pain.

The main takeaway from this image is that the novices demonstrate much higher salience network activation than the meditators before the painful event. Also notably, the degree of brain activation in the novices is pretty much the same whether or not the painful event even happens. By the time that the painful event actually occurs, the novices are already in a state of high anxiety, while the meditators are not.

Citation

Lutz, A., McFarlin, D. R., Perlman, D. M., Salomons, T. V., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Altered anterior insula activation during anticipation and experience of painful stimuli in expert meditators. In NeuroImage (Vol. 64, pp. 538–546). Elsevier BV. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.030