Background Information

Jhana meditation, a practice rooted in Theravada Buddhism, involves entering deeply focused, absorptive states of meditation. It’s characterized by the progressive quieting of the mind, leading to intense states of concentration and bliss. Practitioners move through different levels or “jhanas,” each marked by specific mental qualities such as sustained attention, rapture, joy, and equanimity. This practice emphasizes letting go of sensory input and mental activities to reach states of profound stillness and clarity.

This study, the first to compare brain states between different jhana states, uses both

fMRI

An fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) measures changes in blood flow related to neural activity in the brain, offering insights into brain function and activity patterns.

More on Wikipedia

View in glossary

scans and

EEG

An electroencephalogram (EEG) is a recording of brain activity. During this painless test, small sensors are attached to the scalp to pick up the electrical signals produced by the brain.

More on Wikipedia

View in glossary

recordings to investigate the neural effects of jhana meditation. The researchers hypothesized that jhana meditation would lead to decreased activity in brain regions associated with external awareness, verbalization, and orientation, as well as increased activity in regions related to attention and pleasure. The results supported each of these hypotheses.

What They Did

The authors took EEG and fMRI scans of a seasoned Buddhist meditator (approximately 6,000 hours of meditation experience) as the meditator moved from a restful state through Access Concentration, and the 8 jhanas (J1, J2, …, J8) and then back down to J1. The meditator signalled with a finger tap when he moved between Jhana states. The two scans allowed the researchers to observe:

- Changes in blood flow related to neural activity in the brain, offering insights into brain function and activity patterns (fMRI)

- Electrical activity of the brain, as measured through the EEG.

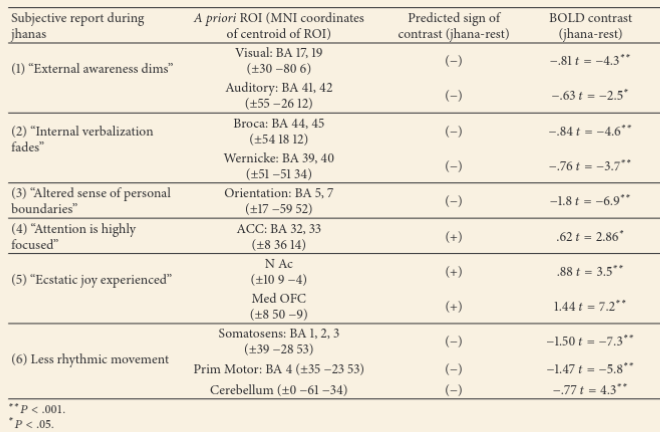

Before running this experiment, the authors had developed a set of hypotheses about what they expected to see in the brain during the jhanas. These hypotheses were based on the subjective experiences of jhana meditation and the authors’ understanding of the brain. These hypotheses were:

- Hypothesis 1: Jhanas should show decreased activity compared to the rest state in the visual and auditory processing areas since all jhanas share the experiential characteristic that external awareness dims

- Hypothesis 2: Jhanas should show decreased activation compared to rest state in brain regions associated with speech since internal verbalization fades

- Hypothesis 3: Jahanas should show decreased activation compared to rest state in the orientation area since the normal sense of personal boundaries is altered

- Hypothesis 4: Jhanas should show increased activation compared to rest state in the areas of the brain related to attention since attention is highly focused during jhana

- Hypothesis 5: Jhanas should show increased activation compared to rest state in the areas of the brain related to pleasure since the jhanas are associated with pleasure

- Hypothesis 6: Jhanas should show no increased activation compared to rest state for the areas of the brain related to phythmic motion and the motor cortex.

One Big Result

Each of the hypotheses were borne out. This table, containing one row for each hypothesis shows the hypothesis in the left column, whether the expectation is that jhana meditation would increase (+) or decrease (-) activity in that brain area, and then on the right the results.

In each of the 11 brain areas, the results matched the predictions of each hypothesis. In the words of the authors:

In the cortical regions associated with external awareness, verbalization, and orientation (H1, H2, and H3), Table 1 shows a lower fMRI BOLD signal during jhana contrasted with rest.

and

In the region associated with executive control (H4) and the region associated with subjective happiness (H5), the fMRI in Table 1 showed higher BOLD signal during jhana contrasted with rest

Thus, it seems that we can conclude from these measurements that jhana meditation quiets the brain (by decreasing awareness, verbalization, and the sense of the boundary of the self), while simultaneously increasing activity in the brain’s pleasure centers and areas associated with attention and self-control.

Miscellaneous Interesting Takeaways

Jhanas are Not Drugs

The authors spend some time discussing possible dangers of absorption meditation, using the language of drug addition:

caution is advisable with any voluntary stimulation of the reward systems. Drugs of abuse can generate short-term bliss but can quickly increase tolerance, requiring ever greater doses of the drug to create the same level of pleasure. They can also create withdrawal symptoms during abstinence

and,

the same reasoning would suggest that the ability to self-stimulate the brain’s reward system would be dysfunctional in the struggle for survival and procreation because it could short-circuit the system that motivates survival actions. Organisms that are adept at self-stimulation would quickly die out if they fail to respond to environmental demands or to pass on their genes. This reasoning suggests caution in making autonomous self-stimulation more available, but we point out that the modern environment already allows unprecedented stimulation of the dopamine reward system with plentiful food and drugs of abuse.

I find it hard to reconcile this language – which equates jhana meditation with a simple sensual high – with the more nuanced view of spiritual pleasure, as presented in meditation handbooks such as Shaila Catherine’s Focused and Fearless:

[the pleasures of the jhanas…] include the delight of non-remorse associated with virtue, the rapture that arises with concentration, the happiness that comes with wholesome states such as love and compassion, the contentment that comes with simplicity and renunciation, the equanimity of tranquil states, and the bliss of release. These feelings are not conditioned by lust, hate, or delusion; they are a vital support for the cultivation of concentration and insight. Invoking these states propels the spiritual journey beyond the conventional confines of sensual experiences.

Different Meditation Techniques Have Different Effects

The authors note their results are incompatible with others performed on meditators performing Metta meditation, a practice of loving-kindness, and also from the effects of transcendental meditation. This is a reminder that different meditation practices have different effects on the brain, and it is likely that the there are a large number of altered mental states achievable using meditative techniques. Unlike the increased gamma synchrony observed by Lutz et al. (2004) during compassion meditation, jhana meditation appears to produce a different neurological signature focused on reward system activation and sensory suppression. For comparison with other meditation techniques, see the work of Maher et al. (2025), which examines the neurological correlates of loving-kindness meditation, revealing increased gamma activity in emotional processing centers.

Citation

Hagerty, M. R., Isaacs, J., Brasington, L., Shupe, L., Fetz, E. E., & Cramer, S. C. (2013). Case Study of Ecstatic Meditation: fMRI and EEG Evidence of Self-Stimulating a Reward System. In Neural Plasticity (Vol. 2013, pp. 1–12). Hindawi Limited. 10.1155/2013/653572