Background Information

The connection between focusing our attention on a task and the random thoughts that pop up when we’re supposed to be concentrating is of great interest, especially in practices like meditation. Specifically, within Buddhism, there’s a strong belief that being able to better control where we focus our attention and being more aware of the tiny shifts in our thoughts can help us recognize and eventually free ourselves from negative thinking patterns. This enhanced mental control and awareness are seen as crucial steps in breaking free from harmful habits of the mind.

That said,

mind wandering

Mind wandering is the spontaneous shift of attention away from a current task or external environment to internally generated thoughts, memories, or fantasies. This common cognitive process is associated with default mode network activation and has been extensively studied in relation to meditation practices, which often aim to reduce mind wandering.

More on Wikipedia

View in glossary

is ubiquitous in every day life. We have all experienced

moving one’s eyes across a page without comprehending a thing

which is suggestive that – for periods of time – our minds can actually wander to the point that we become unaware of our own conscious experience.

One quantitative way to measure mind wandering is through thought probes, which are questions that are asked to subjects during a task to see if their mind is on task or occupied with thought unrelated tasks (TUTs). It has been shown in the laboratory that the presence of TUTs has a distinct neuronal signature, and that TUTs increase errors on tasks by 20%. It has also been shown that TUTs predict performance in more realistic situations like the classroom or everyday life.

In the aggregate, asking somebody if they are experiencing TUTs reveals that on average they’ll answer “yes” 30-40% of the time. The goal of this work is to act as a bridge between laboratory studies and the real world by measuring TUTs for a set of people in both contexts to discover whether mind wandering is a stable characteristic of a person, and whether the context of the activity influences the rate of mind wandering.

What They Did

The authors took 72 college undergraduates, who underwent a sustained attention to response test (SART) in the laboratory, followed some time later by a week-long experience sampling protocol

- Laboratory SART: The SART is a go/no-go task that presented 1810 words for go/no-go responses based on a perceptual (letter case) or semantic (animals vs. foods) discrimination. Subjects were required to press a key for nontarget “go” stimuli (e.g., lowercase words) and withhold responses to infrequent (11%) target “no-go” stimuli (e.g., uppercase words), with thought-probe screens following 60% of the no-go targets to assess the subject’s current thoughts.

- Home Experience Sampling: The home experience sampling involved subjects carrying PDAs (Personal Digital Assistants) for a week, during which they were signaled eight times daily to report immediately whether their thoughts were off task. When signaled, subjects answered questions about whether their current thoughts had wandered from their activity, the content of those thoughts if they had wandered, and their mental and environmental context, using a questionnaire presented on the PDA. This methodology allowed for the collection of data on mind wandering in the subjects’ everyday life activities, providing insights into the frequency and nature of off-task thoughts outside the controlled environment of a laboratory.

The relationships between task performance, and mind wandering both in and out of the lab were then analyzed

One Big Result

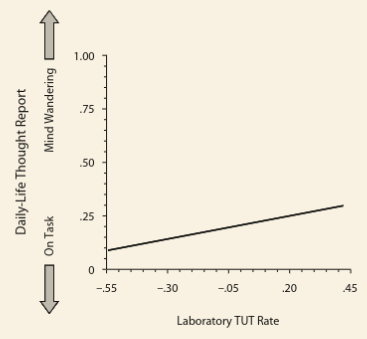

The first result is that the rate of TUTs in the lab predicts the rate of TUTs outside of the lab. The positive correlation in this graph tells us that if your mind wandered more during the lab test, you likely also have more mind wandering in general. Explained by the authors as:

the propensity to mind wander is a stable cognitive characteristic, representing an individual difference that is reliable across time, activities, and contexts

In every-day life, the authors also show that the propensity to mind wander is dependent on the context of the activity. For example, mind wandering is more likely to occur when the activity is boring, stressful, or when there is a lot going on around the subject. On the other hand, mind wandering is less likely to occur when the subject is good at the activity, likes the activity, or when the activity is important.

Miscellaneous Interesting Takeaways

Mind Wandering Never Helps

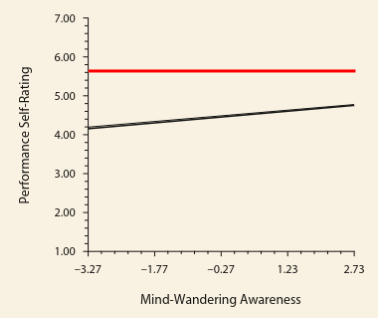

In the field, subjects were asked to rate their performance on tasks whenever they were asked about mind-wandering. Consistent with other studies, subjects’ performance ratings were lower while mind wandering than while mentally on task. Asking subjects about their level of awareness of their mind wandering also revealed that mind-wandering awareness predicted perceived performance. When subjects were aware that they had been mind wandering, they believed they had been performing better than when they had been mind wandering without awareness

The authors noted that

As far as we know, our study is the first to demonstrate a relation between metaconsciousness and human performance in real life.

Mind wandering and the default mode network

This study shows that mind wandering is a stable characteristic of a person, and also that the performance of a person at a task is related to the rate of mind wandering.

There is good evidence that mind wandering is related to activity in the default mode network (

DMN

The default mode network (DMN) is a system of connected brain areas that show increased activity when a person is not focused on what is happening around them. such as during daydreaming and mind-wandering. It can also be active when the individual is thinking about others or themselves, remembering the past, and planning for the future.

More on Wikipedia

View in glossary

), and also that meditation can cause a reducton the activity of the DMN. These observations taken together are suggestive that – through its effect on the DMN – meditation could be used to reduce mind wandering and improve task performance.

Later research by Garrison et al. (2015) demonstrated that experienced meditators show greater reductions in default mode network activity—a neural system associated with mind-wandering—during meditation compared to active cognitive tasks. These findings on the prevalence and stability of mind-wandering complement work by Killingsworth & Gilbert (2010), which revealed the negative emotional consequences of a wandering mind in daily life. Additionally, meta-analytic work by Zainal & Newman (2023) suggests mindfulness training may specifically enhance attention control, which could potentially reduce the frequency or impact of mind-wandering episodes.

Citation

McVay, J. C., Kane, M. J., & Kwapil, T. R. (2009). Tracking the train of thought from the laboratory into everyday life: An experience-sampling study of mind wandering across controlled and ecological contexts. In Psychonomic Bulletin & Review (Vol. 16, Issue 5, pp. 857–863). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 10.3758/pbr.16.5.857